by Caro Silvola

July 17, 2019

Goat-grazing has been gaining popularity in the last decade as private landowners and public parks look for sustainable solutions to clearing buckthorn and other invasive plants. However, there has been very little research to document the effectiveness of goat-grazing or its consequences on plant communities.

Researchers are now catching up with the trend to provide data-driven direction to managers. A cross-disciplinary team – led by Tiffany Wolf of the Department of Veterinary Population Studies and Dan Larkin of the Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology – is working the case from all angles. Their work will measure the impact of goat-grazing on buckthorn and native plant growth, and also address a deadly brain parasite that puts goats in the field at risk.

Researcher Katie Marchetto collects a plant sample in the field as part of her work on the effect of goat-grazing in invasive buckthorn control (Credit: Katie Marchetto)

Data-driven management

Post-doctoral researcher Katie Marchetto has taken the lead in site management and tracking the goats’ impact on buckthorn growth.

“I noticed that people were curious about the effects the goats were having on plant management and when they can and cannot be used,” said Marchetto. “Like me, they were seeing herds being used on public land and wanted to know more.”

One of the first questions to tackle was the basic issue of efficacy. What long-term impact does goat-grazing have on buckthorn growth, and how can it be optimized? Marchetto is seeking an answer with a population growth model, which doesn’t currently exist for buckthorn.

“I noticed that people were curious about the effects the goats were having on plant management and when they can and cannot be used.”

“Some of the things you can do with this type of model is actually see in different populations, which life stages are the most vulnerable to impact. ” said Marchetto, “What age of buckthorn or size of buckthorn should we be really going after to control the population?”

Marchetto’s colleague in the project Sara Nelson, a Master’s candidate in the Department of Conservation Biology, also emphasized the importance of tracking the impact of buckthorn control methods on native vegetation.

“In the restoration community the problem of buckthorn is particularly tricky, as it takes a lot of money and a lot of work,” she said. “It's important to think about what kind of vegetation will replace the buckthorn, and if different management techniques are better or worse at facilitating the recovery of a healthy plant community.”

Community dispatch

Goat Dispatch, a goat-rental based land management company based in Faribault, Minnesota, has been an essential partner in multiple aspects of the team’s research. Owner Jake Langeslag has allowed the team access to his own herd and facilitated communication with his customers for additional research field sites.

Goat Dispatch got its start the day Langeslag decided to rent six goats from his neighbor as an experiment to try and clear his own land of buckthorn.

“I was blown away by how willingly the goats ate the buckthorn, the fun they seemed to be having, and the low hassle once the set-up was complete,” he said.

This led to the development of his own herd for small-scale experiments, which soon caught the attention of nearby landowners.

A buckthorn research plot before (left) and after (right) goat-grazing taken by post-doctoral researcher Katie Marchetto as part of her collaborative work with Goat Dispatch owner Jake Langeslag's herds. (Credit: Katie Marchetto)

Goat Dispatch owner Jake Langeslag presents an overview of using goats to graze brush and invasive plants in a YouTube video. Langeslag is collaborating with MITPPC researchers by allowing his herds to be used in research about goat-grazing and buckthorn control. (Credit: Still image frame from Goat Dispatch YouTube Channel, Jake Langeslag)

Langeslag also views research as critical to his operation's credibility.

"Early on, I was getting some pushback," he said. "People were asking ‘How do we know what you’re doing is good?' And I would say, ‘Well, this is what I see in before and after images.' But we really want data, we want research data. So this works out as a really good partnership.”

“People were asking, 'How do we know what you're doing is good?' And I would say, 'Well, this is what I see in before and after images.' But we really want data, we want research data."

Between running a bustling business and raising a family, Langeslag has also helped found the Ecological Service Livestock Network in partnership with the USDA and Sustainable Farming Association. Formed out of a gathering of fellow Minnesota goat herders, he hopes this new field will grow through collaboration and the sharing of research.

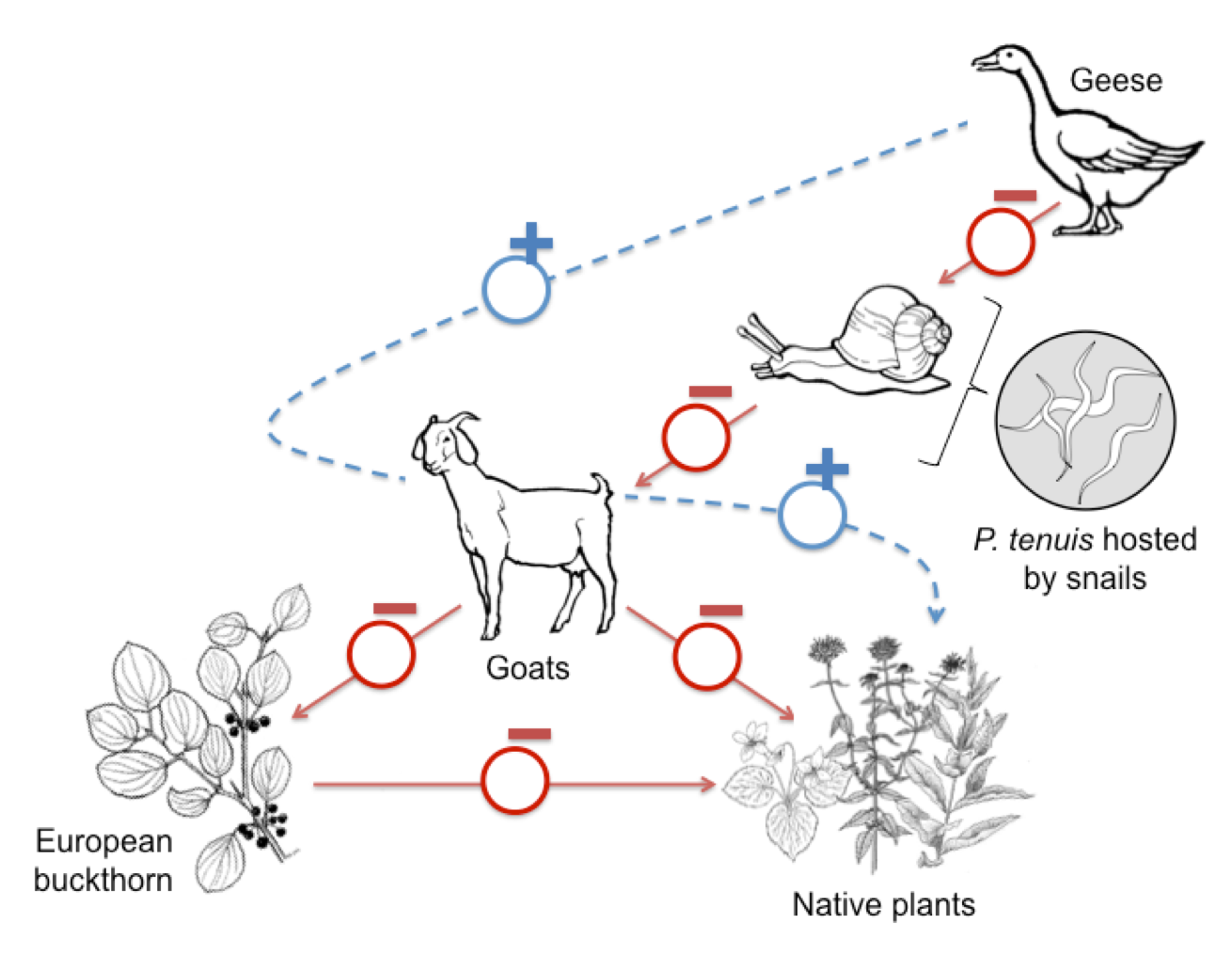

P. tenuis is a deadly parasite that affects goat herds. It is hosted and transmitted by snails that may be present on buckthorn and other plants goats enjoy grazing. Geese and other poultry are not susceptible to the parasite. (Figure provided by Katie Marchetto)

Kids, Meet Poultry

While the future looks bright for goat-grazing, there is one potential set-back for managers.

Parastronguloides tenuis is a deadly snail-and-slug-born parasite that causes slow neurological damage to goats, leading to paralysis and often death. When Langeslag was first getting his business off the ground he lost about 20-30 of his herd to the parasite.

“It’s just a really tough thing to watch. They get paralysis in their back legs and they start dragging and everything else in their body is fine but they just kind of slowly die,” said Langeslag. “And there are some treatments you can give them, but they just are never the same. In my mind, it’s the biggest derailment to the cause.”

Unlike goats and other mammals, birds are not susceptible to P. tenuis. Some have therefore suggested the introduction of poultry as a strategy for managing the risk of parasitic infection in herds. By feeding on the slugs and snails that serve as intermediary hosts to P. tenuis, poultry like ducks and geese could reduce the transmission of the parasite to grazing animals.

However, research-backed data on the effectiveness of this strategy to date has been limited. The team will actually be the first to test this method on a goat-grazing system.

Wolf, the team’s lead, has studied the paralysis-causing meningeal worm in Minnesota moose populations for years.

“Exploring the role of geese and ducks as an approach to mitigating transmission to pastured livestock like goats and alpacas is a great alternative to the only other means of mitigation and control that we have, which is using anti-parasitic drugs,” she said. “We know that overusing those can cause resistance to those drugs in other parasitic worms, which also impact the health of the livestock infected.”

Wolf and her team have teamed up with the Dakota County 4-H for poultry expertise. Families within the project will raise and train ducklings for the pre-grazing strategy. UMN Extension and County 4-H Program Coordinator Anja Johnson has helped connect the project with excited families.

“I think it’s an amazing opportunity for the kids. We often talk about higher implementation, and having them involved provides a great experience in exploration and hands-on learning,” she said.

Katie Marchetto tweets a video of the ducks raised by Dakota County 4-H students and their

families for invasive species research. (Credit: @GreenWorldHypo)

About the Author

Caro Silvola is a Communications Intern with the Minnesota Invasive Terrestrial Plants and Pests Center (MITPPC). She is a double major in Bioproducts & Biosystems Engineering and English Literature and is highlighting research-community partnerships in the summer of 2019. Outside of the office, Caroline likes biking, making art, exploring, volunteering in her community and participating in environmental movement spaces.