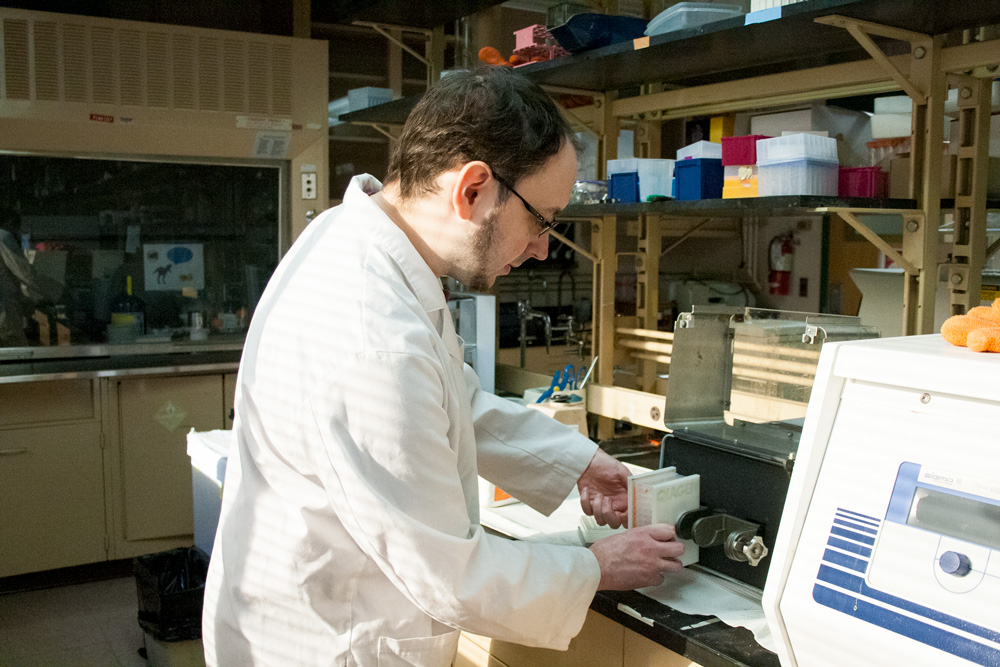

Anthony Brusa is part of an MITPPC-funded team led by agronomist Don Wyse.

SPOTLIGHT SERIES

Post-Doctoral Associate | he/him/his

Can you give a quick overview of your work with MITPPC?

We're developing methods of detecting high-impact invasive Palmer amaranth through genetic markers. There are a number of pigweed species that are difficult to tell apart. Palmer amaranth is a really high priority one, and we're trying to prevent it from spreading. So, we're using genetic testing to identify Palmer and distinguish between [pigweeds], even though they are very, very similar looking.

About the Author

Maggie Nesbit is a Communications Intern with the Minnesota Invasive Terrestrial Plants and Pests Center (MITPPC). She is a double major in English and Strategic Communications at the University of Minnesota. In her spare time, Maggie enjoys running, hiking, reading and spending time with friends and family. Maggie's position is funded by a grant from the Minnesota Soybean Research & Promotion Council.