by Carolyn Bernhardt

August 14, 2023

To Robert Blanchette, a professor in the Department of Plant Pathology in the College of Food, Agriculture and Natural Resource Sciences, the state of Minnesota needs a biosurveillance program—urgently. “It's a way to find pathogens early, stop their movement, and limit their impact,” he says.

And Nickolas Rajtar, a PhD candidate in Blanchette’s lab, agrees. “It's vital to do this, because we don't want to have another horror story, like we've seen with the Dutch elm disease, and the emerald ash borer,” he says.

That’s why the lab focuses on developing novel tools for proactively detecting and managing deadly, invasive plant pathogens before they can rip through Minnesota’s forests. “There isn't any formal biosurveillance team in Minnesota,” says Rajtar, “but [our team does] a lot of collaborations with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA) and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR).”

A collective pursuit

Rajtar’s master’s work in the Blanchette lab tracking and understanding the fungal communities carried to and around forests by the invasive emerald ash borer (EAB) helped set him up to lead a new pathogen biosurveillance project for his PhD—identifying and managing diseases caused by Heterobasidion and Phytophthora.

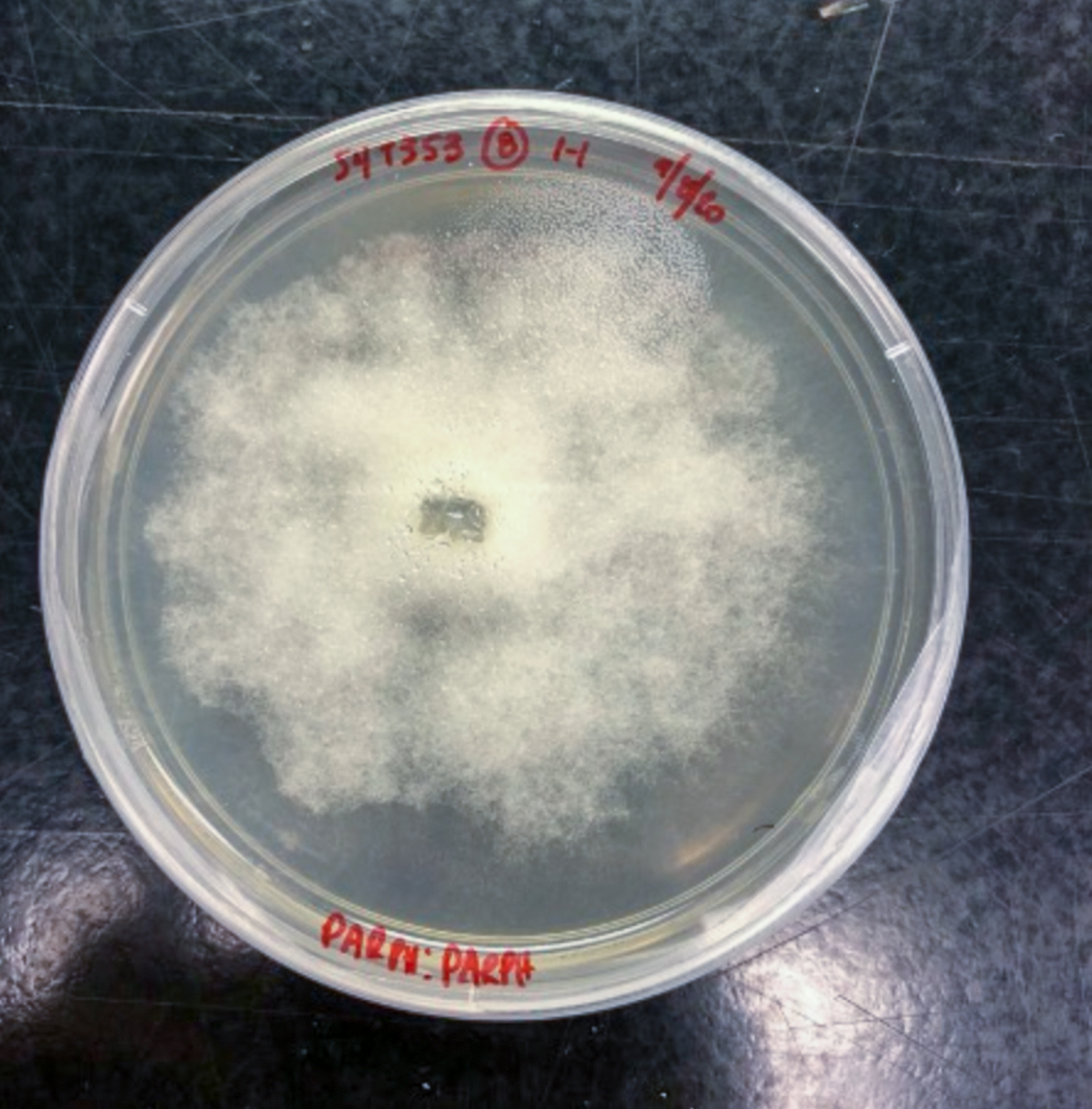

Phytophthora is a genus of plant-pathogenic oomycetes (water molds) that attack the roots and stems of trees, causing various diseases and leading to symptoms such as root rot, wilting, dieback of branches, and ultimately, tree death. Phytophthora species are responsible for significant damage to forests, orchards, and ornamental trees in Minnesota and worldwide.

Heterobasidion causes a serious tree disease known as root rot in coniferous species. “It often affects trees in plantations, causing substantial financial hardships for those dependent on them,” Rajtar says. “Once it takes hold, the fungus kills the tree and moves to the adjacent trees underground, causing circles of tree death.”

Researchers found Heterobasidion in southeastern Minnesota in 2014, and the Minnesota DNR swiftly eradicated it. Blanchette says, “Our lab hopes the detection tools we are using will find new infection sites and help keep the invader at bay.”

Tracking and testing Phytophthora

In his search for Phytophthora species, Rajtar is working with the MDA, who helps him gather samples from nurseries and Christmas tree plantations across the state. “To date, we've processed over 1,000 samples of soil and woody plant tissue [since we began in 2020],” Rajtar says. They have identified 21 Phytophthora species, 13 of which hadn’t yet been reported in Minnesota.

Rajtar and his collaborators take samples from nursery soil and nearby waterways back to the lab and use bait traps to coax the Phytophthora out of the sample. That way, the team can isolate the pathogens and track their movement. Researchers and managers alike can use this information to outstep Phytophthora’s advance across the state and introduce management tactics before the pathogen can cause the damage it has the potential to.

The next step in the team’s research, Rajtar says, is testing each Phytophthora species’ ability to cause disease on different trees or plants. This information can help inform how experts allocate their time and resources to tackle the pathogen. Blanchette is also eager to monitor whether these newly found species have spread beyond nurseries and naturalized elsewhere so researchers can introduce management tactics wherever necessary.

Hunting a hidden pathogen

In contrast, Heterobasidion lurks below the soil, traveling through roots and spreading rapidly to infiltrate the trees in its path. Its difficult-to-detect nature makes it a significant threat to the health and sustainability of forests.

“Wisconsin has lots of this disease,” Blanchette says, “So, we are using spore traps to see if there are any new infection sites all along that eastern front where Minnesota borders Wisconsin.”

Blanchette hopes to gain assistance from the Minnesota DNR in pursuing areas where spores are showing up to pinpoint exactly where the infections are and new root rot centers are located. The fieldwork for this effort involves identifying forest openings and dead standing trees, which may require satellite imagery and on-the-ground exploration.

It takes time for the fungus to manifest visibly, Blanchette says, so the team needs to cut into the trees and get samples for isolations to confirm the presence of the pathogen. That fieldwork is slated to start later in the summer of 2023 and comprises a significant component of phase two of the research.

In this whole process, the team has also evaluated which traps are the most effective for different contexts. Blanchette points out that the spore traps also provide valuable data on other invasive pathogens coming into the area, not just Heterobasidion. Rajtar and team have not found any significant new pathogens just yet, but they continue to monitor for potential threats like Ash decline, sudden oak death, pitch canker, European large canker, and other invasive species ranked on the priority list of the Minnesota Invasive Terrestrial Plants and Pests Center (MITPPC).

Hope for our forests

Rajtar says his primary goal is to safeguard the forests for future generations to enjoy. “Early detection of these pathogens is crucial for mitigating or controlling their impact before it becomes overwhelming,” he says. “We have the technology, now we must implement and utilize it effectively.”

“We're very fortunate to have the funds from MITPPC,” says Blanchette. “Because without those, none of this work would be done, and we would not be able to monitor or stop these invasive pests before they cause widespread damage.”

Photos for this story were provided by Robert Blanchette and Nick Rajtar.

The Minnesota Invasive Terrestrial Plants and Pests Center research is supported by the Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund, as recommended by the Legislative and Citizen Commission for Minnesota Resources.

Stay connected by signing up for the MITPPC newsletter or follow us on Facebook or Twitter.